Change in the air, change on the ground?

After nearly two years of disruption, no one can avoid the transformations in global travel, public health and industry transformation. Now might seem like a perfect storm - the confluence of a pandemic, growing climate change concerns, and continuing waves of technological innovation and change.

Here in the heart of Southeast Asia, Singapore has a reputation for looking and thinking ahead, planning for the needs and benefits of its population and economy beyond the immediate noise of current events. Education, industries and jobs factor heavily in those considerations, and the government agencies have been investigating and pursuing directions for meeting current and future needs. Specific to both the city state’s needs and future potential, identifying three (3) key sectors, the Government of Singapore has defined and highlighted;

1. The digital economy

2. The green economy

3. The care economy

These are distinct growth areas that offer substantial and positive commercial, social and environmental opportunities. It is a clever distinction, highlighting clear and specific needs in the market and society. There are also many overlaps because every business has a digital dimension, and every industry has a green impact to address.

Sustainability - a foundation for the whole future economy

Rising out of these current national and global circumstances, the ideas of “adaptation”, “sustainability”, and “resilience” figure more strongly than ever. These are also mirrored in the wider Environment Social and Governance (ESG) agenda, which is reflected in many industry and business forums.

Having been part of a separate landscape industry transformation review only eighteen months ago, how can the profession of Landscape Architecture respond? In response to the Government’s key areas of focus, how can Landscape Architects interact more successfully within these growth areas?

One answer is to avoid only looking at the obvious ‘green economy’ but seek opportunities within the virtual world, the growing digital economy, and the care economy! Utilizing urban data and analytics in design of the urban landscape is one such opportunity. Contributing to innovative environmental treatments and measurement of performance in the emerging new green economy and shaping both environments and programmes that support the care economy is another.

Progressive landscape Architecture for this century’s challenges

Looking at the identified growth areas, industries' needs and core skills highlighted in the SkillsFuture report, we can spot three broad approaches that Landscape Architects and our profession could embrace fully to take advantage of the needs and opportunities.

1. Ditch the decorative

The Government’s updated Singapore Green Plan 2030 points the way. Moving towards a city environment that uses less energy, reduce carbon emissions, enhance spaces and connections for human activity and improves open space functions efficiently. Creating real, measurable values: social, environmental, and ecological values that are understandable for people.

The case for landscape architecture and the urban landscape is apparent, stop designing maintenance-heavy schemes and harness the power of natural systems and naturalization. Instead, move towards more innovative, flexible external space uses and push for better green connections between existing remnants, reserves, parks and waterways.

However, the opportunities do not stop there. Across the three targets, there are clear examples of other sectors and areas where the urban landscape could deliver. For example, better health benefits for the public, wider environmental co-benefits like urban cooling, better coastal edges for biodiversity and resilience to flooding and even a greater level of renewable energy generation within the public property are all potential avenues.

2. Diverse and flexible design skills

Here the possibilities are most straightforward and most specific. As a design profession, we already use technology in the form of software applications, communications and business management. But how many in the profession actively engage with evidence-based design, computation design or performance simulations beyond the visual aesthetics? Intuitive design only reflects our personal views. Generating spatial patterns does not automatically demonstrate value or performance.

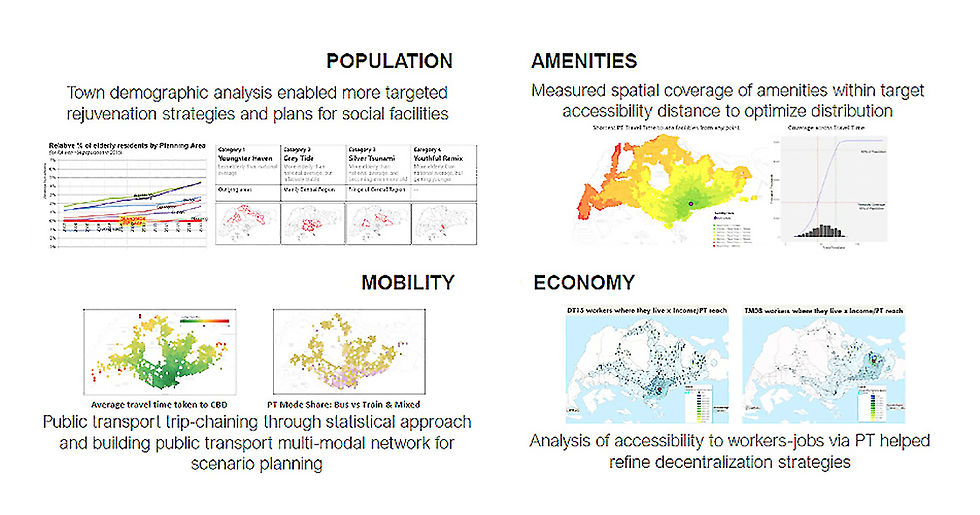

Digitization of site information is only the first step. Digitalization means a transformation in the design process that plugs the landscape professions into a host of rich data, allowing a broader perspective in design for specific and valuable purposes and a baseline for measurement (or initial design simulation) of the urban landscape’s actual performance.

We could take a leaf from the BIM platform creators and develop a complementary LIM (Land/Landscape Information Modelling) platform. We can focus more on the urban and landscape aspects of the city environment, like urban heat, micro-climates, drainage, pedestrian and PMD connectivity, and water and vegetation design of the urban landscape.

And, we should look beyond the built environment sector. These skills range across different sectors of the economy and environment. They are readily applicable and undoubtedly valuable to the digital economy and the public health aspects of the care economy.

3. Managing dynamic environments

What highly dense cities, large populations and immediate nature/urban proximities all face is the need for active management. To protect, nurture and sustain different competing demands and preserve irreplaceable natural environments. We are searching for a healthier balance between development and nature, construction and preservation, between people and the environment.

The maintenance and management of the urban landscape have been a source of frustration for many. Undervalued frequently led to driving down costs and poorer quality. Clearer performance requirements (like carbon and GHG data, urban heat and water management) wrapped in certification and regulatory approvals can lead to this neglected aspect of the urban landscape and environment being highlighted, understood, and finally measured and monitored and valued. The environmental management in landscape operations, with a heavy emphasis on the “environmental”.

Here we need to expand beyond spatial design to embrace programming of spaces, activities, environmental quality and ecological (also read biodiversity) value. An example from the care economy might be sufficient to illustrate this point. Designing and developing both spaces, activities like “horticultural therapies” for a specific community with programmes of engagement that boost the quality of life through aiding and maintaining cognitive, psychological, social interactions and physical abilities.

Specific roles are already identified (in very different industry sectors), ranging from irrigation management, smart facilities management (which needs to extend from just “green buildings”) to healthcare and social service programming. The smart management of the city’s social spaces, open spaces, parks, and green infrastructure offers a whole new dimension.

Opportunities and challenges ahead

Recently, an article claimed that the emerging green economy jobs required only generalist knowledge and little or no technical skills. Although well-meaning, this simplistic explanation is misleading. Public concern on climate issues, greenhouse gas emissions, and global biodiversity loss has captured media attention, garnered business reaction and even shifted political opinion. As a result, there is now an agenda for action.

While this positive movement is growing, it also brings a tidal wave of information and opinion, much of which is misinformed. As a result, the likelihood of ‘greening washing’ also grows with it. It requires experienced and knowledgeable Landscape Architects who are informed and articulate to sift through the well-meaning, and inaccurate as we promote and share best design practices, new design innovations, technological tools and application software in our profession.

The Singapore Institute of Landscape Architect’s Council is investigating new professional development collaborations with Singapore’s Design Council on a brand new initiative, the Design Education Action Committee which promotes collaboration of the academic, research and teaching faculties with industry and professional bodies like SILA, to speed these positive goals into action and application.

The challenge is on for Landscape Architects and the profession in Singapore.

By Simon Morrison

Co-Founder and Director at Field Labs and SILA Council Member

Comentários